ITL #635 Auspicious semiotics: Chinese consumer psychology

7 months ago

Savvy marketers find various ways of tapping into a uniquely Chinese blend of symbolism, language, and superstition. By Edwin So.

The recently concluded Gaokao (National College Entrance Examination) is a momentous event for millions of families across China. Held every June, it is a pivotal test that can shape a student’s entire future. Unsurprisingly, the intense pressure surrounding the exam often spills over to the parents, who become deeply anxious during this period.

This anxiety has even fueled a quirky trend: The popularity of certain symbolic items believed to bring good luck. For instance, some mothers dress in traditional qipao to escort their children to the exam venue, drawing on the phrase “qikai desheng”—which literally means “to win from the very start.” Fathers may wear a magua (a traditional jacket), as a nod to the phrase “madao chenggong”, or “instant success.”

This phenomenon offers a glimpse into one of the most enigmatic and culturally nuanced aspects of marketing and branding in China—what I call Auspicious Semiotics. It is a uniquely Chinese blend of symbolism, language, and superstition.

Deeply embedded in both written and spoken Chinese, its interpretations can become even more layered and diverse due to the country’s many dialects. In fact, the same symbol can carry vastly different meanings across regions.

A personal example

Let me share a personal example. I’m originally from Hong Kong, where Cantonese is my native language. I relocated to Beijing in my thirties and have lived here for over three decades, now primarily speaking Mandarin.

In Beijing and much of northern China, shop names often feature the character “鑫”—composed of three “金” (gold) radicals—symbolizing wealth and prosperity. But in Hong Kong and other Cantonese-speaking regions, this character is rarely used. It’s not only difficult for Cantonese speakers to pronounce, but also visually complex.

Instead, southern businesses tend to favor the character “发” (fa, meaning “to prosper”) or the number “8,” both of which sound like “making a fortune” in Cantonese.

Another example comes from the world of watches. In Cantonese regions, many self-made entrepreneurs from older generations wear gold Rolex watches—not necessarily as a display of wealth, but because the nickname “金劳” (Gold Rolex) sounds like “襟捞” in Cantonese, which conveys the meaning of “continuously being able to get business”.

This kind of phonetic symbolism can also work against a brand. Before the smartphone era was dominated by iPhone, Samsung, and Huawei, brands like Nokia, Ericsson, and Motorola were household names. However, Motorola faced resistance in Cantonese-speaking markets because its name sounded like “无得捞啦”—which roughly translates to “no more business” or “no work to do”— An ominous connotation for superstitious users.

Taking a “hotpot” approach

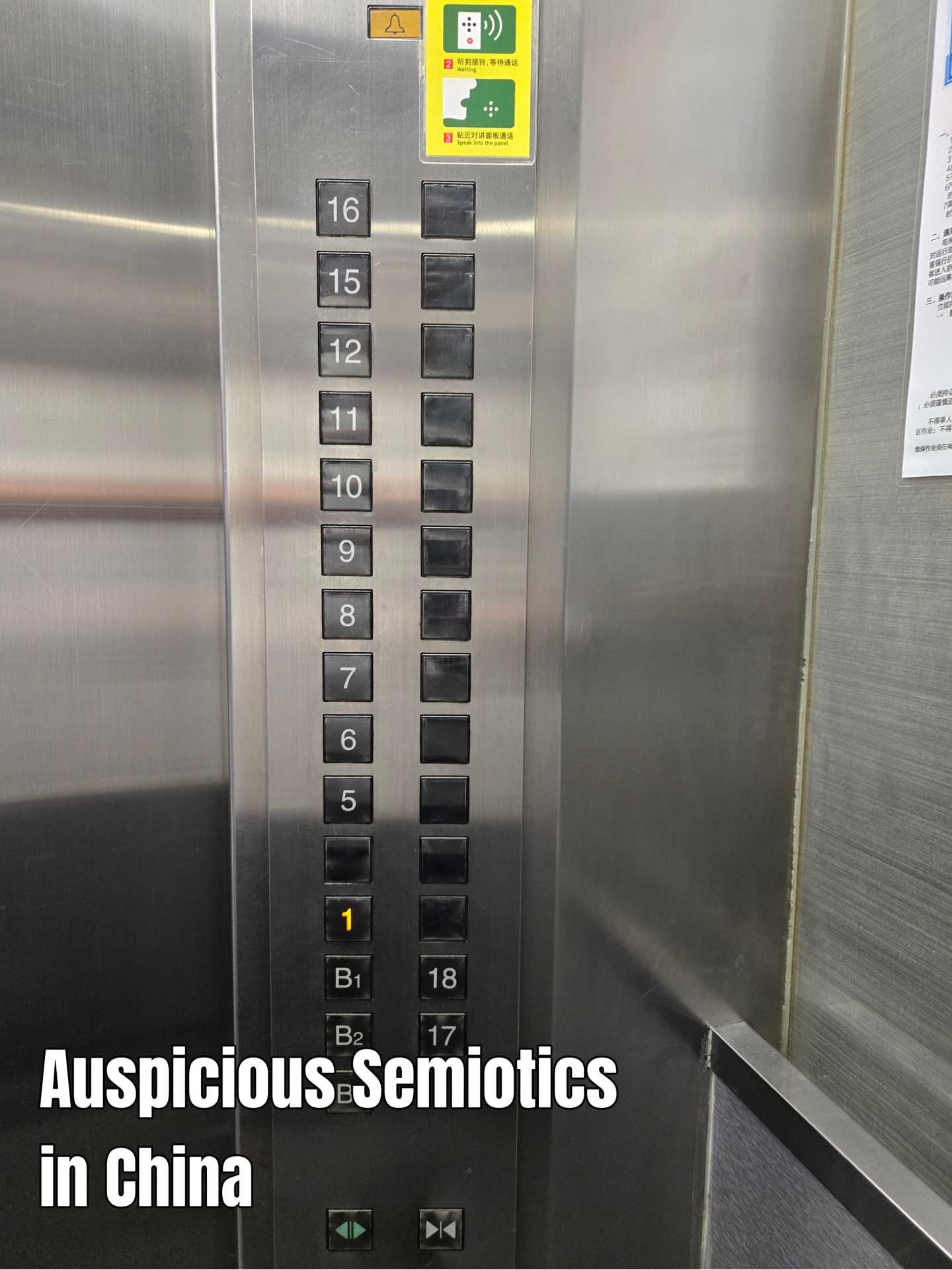

Given how deeply rooted and complex Auspicious Semiotics can be—shaped by dialects, traditions, and even foreign cultural influences—some marketers in China take a “hotpot” approach: Mixing multiple symbolic cues to appeal to as many audiences as possible. Take the building where my Beijing office is located, for instance. It’s a 30-plus story tower with four elevators divided for high and low floors.

The cut-off point is the 18th floor—the highest stop for the lower elevators—chosen because “18” sounds like “certain to prosper” in Chinese. The upper floors symbolize rising success.

If you look closely at the elevator control panel image above, you’ll notice that there’s no 4th or 14th floor—since the number “4” sounds like “death” in both Mandarin and Cantonese, and “14” even more ominously resembles “sure to die.” Interestingly, there’s no 13th floor either, in keeping with Western superstitions.

This seamless blending of Chinese and Western cultural sensitivities illustrates just how intricate—and at times bewildering—the world of Chinese consumer psychology can be.

The Author

Edwin So

Edwin So, Managing Director, Paradigm Communications. A business communicator working in Greater China for four decades.

mail the authorvisit the author's website

Forward, Post, Comment | #IpraITL

We are keen for our IPRA Thought Leadership essays to stimulate debate. With that objective in mind, we encourage readers to participate in and facilitate discussion. Please forward essay links to your industry contacts, post them to blogs, websites and social networking sites and above all give us your feedback via forums such as IPRA’s LinkedIn group. A new ITL essay is published on the IPRA website every week. Prospective ITL essay contributors should send a short synopsis to IPRA head of editorial content Rob Gray emailShare on Twitter Share on Facebook

Authors

- Aaron E. Boles

- Abigail Levene

- Aco Momcilovic

- Adam Harper

- Adam Rubins

- Adedoyin Jaiyesimi

- Advita Patel

- Aedhmar Hynes

- Agustín de Uribe-Salazar

- Akemi Ichise

- Alain Grossbard

- Alain Modoux

- Alan Lane

- Alan Tyrrell

- Alasdair Townsend

- Alberto Melida

- Alejandro Butler

- Alexander Christov, PhD

- Alexander Fink

- Alex He

- Alia Papageorgiou

- Alice Thomas

- Alison Arnot

- Alison Jefferis

- Alistair McLeish

- Alistair Nicholas

- Alistair Peck

- Allan Biggar

- Allison Slotnick

- Amanda Coleman

- Amanda Glasgow

- Aman Gupta

- Amit Misra

- Amybel Sánchez de Walther

- Amy Shanler

- Amy Thurlow

- Amy Wahome

- Ana Adi

- Anders Monrad Rendtorff

- Andrea Anders

- Andrea Cornelli

- Andrea Gissdal

- Andrea Neumann

- Andreas Hammer

- Andres Wittermann

- Andrew Adie

- Andrew Ager

- Andrew Blum

- Andrew Graham

- Andrew Grant

- Andrew Greenlees

- Andrew Griffin

- Andrew Mackay

- Andrew Marshall

- Andrew Mckenzie

- Andrew Sedger

- Andy Green

- Andy Pharoah

- Andy Philpott

- Andy Rowlands

- Angela Jeffrey

- Angela Scaffidi

- Angele Giuliano

- Angeles Moreno

- Angélica Consiglio

- Aniisu K Verghese Ph.D.

- Anja D’Hondt

- Anja Feuerabend

- Anna Krajewska

- Anna Ruth Williams

- Anne Bahr

- Anne Bleeker

- Anne Costello

- Anne Dorte Bach

- Anne Gregory PhD

- Annie Mutamba

- Ann Marie Gothard

- Ann Whyte

- Anthony D’Angelo

- Antonio Rodrigo Sanmartín

- Anton Nebbe

- Archana Jain

- Armand Maris

- Armin Huttenlocher

- Arnaud Pochebonne

- Arthur E.F. Wiese, Jr.

- Arunava Khan

- Arwa Husain

- Ashford Pritchard

- Ashraf Shakah

- Ashwani Singla

- Astrid von Rudloff

- Athena Wang

- Ava Lawler

- Ayelet Noff

- Barbara Crowther

- Barbrha Ibáñez

- Bart de Vries

- Benaja Nkemzikann

- Ben Finzel

- Benjamin Haslem

- Ben Maynard

- Ben Petter

- Ben Petter

- Ben Rachel

- Beth Garcia

- Bianca Ghose

- Bidemi Zakariyau

- Bill Cowen

- Bill Margaritis

- Bill Royce

- Binda Rai

- Blair Peberdy

- Bob Grove

- Bob Pickard

- Borja Iglesias

- Bosco Marti

- Brendan Bracken

- Brendon Craigie

- Brian Moriarty

- Bridget Marcou

- Bronwen Andrews

- Bruce Berger

- Bruce Coppa

- Bryan Harris

- Bryan H. Reber

- Burghardt Tenderich

- Burton St. John III

- Camilla Flatt

- Camilla Lercke

- Candice Teo

- Carbo Yu

- Carlo Ennio Stasi

- Carlos A. Mazalán

- Carol Borchert

- Carol Levine

- Carolyn Tieger

- Caryn E. Medved

- Caterina Cazzola

- Catherine Arrow

- Cayce Myers, Ph.D., LL.M., J.D., APR

- Cem Ýlhan

- Ceyda Aydede

- Charlotte Chunawala

- Charlotte West

- Chek Yee

- Cheryl Krauss

- Cheryl Moore

- Chris Atkins

- Chris Bailey

- Chris Dobson

- Chris Genasi

- Chris Owen

- Christal P. McIntosh

- Christiaan Prins

- Christian Krpoun

- Christina Forsgård

- Christina Kim

- Christine Barney

- Christine L Ammunson

- Christof Ehrhart

- Christophe Ginisty

- Christopher D. Cathcart

- Christopher Storck Ph.D

- Christoph Schwartz

- Christoph Schwartz

- Ciro Dias Reis

- Claire Spencer

- Claire Walker

- Clāra Ly-Le Ph.D.

- Claudia Gioia

- Claudia Macdonald

- Claudia Pritchitt

- Claudia Wittwer

- Claudine Moore

- C Lekha

- Colette Ballou

- Colin Shevills

- Cortney Stapleton

- Courteney Jung

- Craig Badings

- Crispin Manners

- Curtis Sparrer

- Daisy Pack, HUNTER

- Dale Fishburn

- Dale Lovell

- Damien Ryan and Lauren Goble

- Damon Hunt

- Dana Oancea

- Daniel Kent

- Daniel Rolle

- Daniel Silberhorn

- Daniel Tisch

- Daniel Verpeaux

- Danijel Koletić

- Danny Cox

- Dan Perlet

- Dan Rolle

- Daphne Liew

- Dave Heinsch

- Dave Robinson

- David Alexander

- David Amerland

- David Brain

- David Croasdale

- David Eisenstadt

- David Fine

- David Fraser

- David Huerta

- David Ketchum

- David Landis

- David Lian

- David Liu

- David Remund

- David Zucker

- Dean Kruckeberg

- Dean Kruckeberg Ph.D.

- Debbie Hindle

- Deb Camden

- Deborah Charnes Vallejo

- Deborah Gray

- Deepa Dey

- Deeped Niclas Strandh

- Deepshikha Dharmaraj

- Dejan Verčič and Ansgar Zerfass

- Delia Sieff

- Delphine Jouenne

- Dennis de Cala

- Dennis Landsbert-Noon

- Dennis Larsen

- Derrick Pieters

- Dessislava Boshnakova

- Diana Verde Nieto

- Dian Wahlen

- Didier Lagae

- Dilip Cherian

- Dimitri Schildmeijer

- Dionne Clemons

- Djohansyah Saleh

- Dorle Riechert

- Dr. Ron F. Jabal

- Dr Sabine Hückmann

- Dr. Tony Jaques

- Dr. Zizheng Yu

- Dustin Chick

- Duygu Cavdar

- Edd Fuentes

- Edwin So

- Eike Alexander Kraft

- Eirik Øiestad

- Elaine Cameron

- Elaine Cruikshanks

- Elena Baikaltseva

- Elena Fadeeva

- Eleonora Leone

- Elina Melgin

- Elisabeth Hilsdorf

- Eliza Hazlerigg

- Ellen Gunning

- Ellen Lubell

- [email protected]

- Ellen Raphael

- Emily Teitelbaum

- Emma Dale

- Emma Dale

- Emma Johnson

- Emma Kane

- Emma Kelly

- Emmanuel Goedseels

- Emma Richards

- Eric Dragt

- Erika Pope

- Erik Jonnaert

- Erik van de Nadort

- Ernst Primosch

- Esmé Gibbins

- Esther Cobbah

- Eszter Szabo

- Etsuko Tsugihara

- Evadney Campbell

- Eva Sogbanmu

- Eva Torra

- Evelyn John Holtzhausen

- Faith Senam Ocloo

- Farzana Baduel

- Firas Sleem

- Flavia Bonfá

- Founder & CEO, SlicedBrand

- Francesca Concina

- Franco Giacomozzi

- Francois Baird

- Frank G. Kurzhals

- Frank Ovaitt

- Fraser Hardie

- Gabrielle Gambrell

- Gail Cohen

- Gail S. Thornton

- Garry Lockwood

- Gary Wells

- Gavin Haycock

- Gene Marbach

- Genevieve Hilton

- George Affleck

- George Allen

- George Flessas

- George Noon

- Georgios Kotsolios

- Georg Lahme

- Gerd Götz

- Gergana Vassileva

- Gerry Griffin

- Gerry McCusker

- Giles Fraser

- Gillian Findlay

- Girish Balachandran

- Giselle Bodie

- Glenn Schloss

- Gordana Bekčić Pješčić

- Gordon Coulter

- Graeme Domm

- Graham Goodkind

- Graham Goodkind

- Greg Haas

- Gregory Cole

- Greg Wright

- Guðjón Heiðar

- Guðjón H Pálsson

- Guillaume Herbette

- Gustavo Averbuj

- Guy Esnouf

- Guy Versailles

- Guy Walsingham

- Hannah Patel

- Hansch van der Velden

- Harald Bråthen

- Haroon Sugich

- Harriet Mouchly-Weiss

- Heath Applebaum

- Heather Astbury

- Heather Chambers Knox

- Heather Kernahan

- Heikki Sal-Saller

- Hélène V. Gagnon

- Hemant Batra

- Henriette Viebig

- Hil Berg

- https://www.ipra.org/dashboard/my_cms/itle/add/

- Hubert Wisse

- Iain Burns

- Ian Herbison

- Ian Rumsby

- Ilissa Miller

- Illka Gobius

- Ina Nikolova

- Indira Abidin

- Inge Wallage

- Ingmar de Gooijer

- Inna Alexeeva

- Ivan Jaksic

- Jacek Jakubczyk

- Jacek Ławrecki

- Jackie Cooper

- Jack Pearce

- Jacqueline Purcell

- Jacquie L’Etang

- Jaideep Shergill

- James Crawford

- James Duffy

- James Lakie

- James Lukaszewski

- James Lynch

- James McQueeny

- James Savage

- James Thellusson

- James Weeks

- Jamie X Oliver

- Jane Hammond

- Jane Stabler

- Janet Kabue-Kimani

- Janine Allen

- Jason Schlossberg

- Jean-Michel Dumont

- Jean-Pierre Beaudoin

- Jeff Chertack

- Jeff Risley

- Jennifer Hardie

- Jennifer Hawkins

- Jennifer Janson

- Jennifer Leppington-Clark

- Jenni Field

- Jenny Hoefliger

- Jens D. Mueller

- Jens Seiffert-Brockmann Ph.D.

- Jeremy Galbraith

- Jeremy Galbraith

- Jessica Adelman

- Jessica M. Graham

- Jessica Van Onselen

- Jill Dosik

- Jim Donaldson

- Jim Kerr

- Jim Surguy

- Jim Walsh

- Jirimiko Oranen

- Joachim Klewes

- Joanna Oosthuizen

- Joanne Kennedy

- Jo Crawshaw

- Jodi Olson

- Joe Cohen

- Joerg Mueller-Duenow.

- Johan Melchior

- Johanna McDowell

- John Bailey

- John Digles

- John Foster

- John Gilfeather

- John Maroon

- John McLaren

- John Orme

- John Russell

- John Seng

- Jonas Jonell

- Jonas Rodny

- jonathan Hemus

- Jonathan Hemus

- Jonathan Sanchez

- Jonathan Shillington

- Jonathan Simnett

- Jonathan Smith

- Jonathan Wilson

- Jon Meakin

- Jonne Ceserani

- Jon van Dongen

- Jon White

- Jorge Acosta

- Jörg Pfannenberg

- José L. Ibarra

- Joseph A. Brennan Ph.D.

- Joseph John Nalloor

- Joshua Van Raalte

- Joshua Van Raalte,

- Joy Scott

- Juan-Carlos Molleda

- Juan-Carlos Molleda

- Juan F. Lezama

- Judith Hamblyn

- Judith Moore

- Judith von Gordon

- Julia Cartwright

- Julia Harrison

- Julia Hobsbawm

- Julia Stonogina

- Julia Willoughby

- Julie Atherton

- Julie Exner

- Julie Gaye

- Jutta Lorberg

- Kaija Langenskiöld

- Kara Alaimo Ph.D

- Karena Crerar

- Karen Reina

- Karin Lohitnavy

- Karl G. Rickhamre

- Kate Alexander

- Kate Dobrucki

- Kate Hartley

- Kathryn Goater

- Kathy Guillermo

- Kathy Tunheim

- Katie Delahaye Paine

- Katie Spreadbury

- Katrina Nevin-Ridley

- Katy Howell

- Kavita Rao

- Kazuko Kotaki

- Keisuke Maeda

- Keith Hunt

- Kelley Murray Skoloda

- Ken Hong

- Ken Jacobs, PCC, CPC

- Ken Mandelkern

- Kerrie Finch

- Kerry Sheehan

- Kevin Dorrian

- Kev O’Sullivan

- Khamisi McKenzie

- kimberley Goode

- Kimberly Cohen

- Kim Blanchette

- Kim Kyong-Hae

- Kimon Antypas

- Kiri Sinclair

- Kirk Hazlett

- Koenraad van Hasselt

- Koichi Iwasawa

- Korinna Penndorf

- Kristian Eiberg

- Kristiina Tolvanen

- Kristina Blissett

- Kristy Nicholas

- Krystyna Cap

- Kumi Sato

- Lak Siriwardene

- Lars-Ola Nordqvist

- Laura Evans Manatos

- Laura Hawksworth

- Laura Hindley

- Laura Romain

- Laura Schoen

- Laurence Lee

- Lavanya Wadgaonkar

- Lee Nugent

- Leif Geiger

- Lena Soh-Ng

- Leo Rayman

- Lerato Malimabe

- Leslie Gottlieb

- Libby Howard

- Li Hong

- Lisa George

- Lisa Kimmel

- Lis Anderson

- Lisa Vallee-Smith

- Liz Kamaruddin

- Louay Al-Samarrai

- Louise O’Brien

- Louise Roberts

- Louise Robertshaw

- Loula Zaklama

- Lucas Bernays

- Luciano Luffarelli

- Luc Missinne

- Lucy Siegel

- Luis Avellaneda Ulloa

- Lukasz Wilczynski

- Lutz Meyer

- Lydia Buchtmann

- Lydia Lee

- Lydia Lei Lee

- Lyle Closs

- Lynette Jackson

- Malcolm McDonald

- Malcolm Padley

- Marci Kaminsky

- Marcus Brewster

- Marek Beneš

- Margaret Key

- Maria Gergova

- Mariana Sanz

- Marianne Eisenmann

- Marian Salzman

- Marian Salzman

- Maria Rivas-McMillan

- Maria Speridakos

- Maril MacDonald

- Marina Bolanča

- Mario Ambrosi

- Marjie Hadad

- Mark Crompton

- Mark Giles

- Mark Hass

- Mark Herford

- Mark Hunter LaVigne

- Mark Nardone

- Mark Sheehan

- Mark Stephenson

- Mark Tungate

- Markus Berger

- Martina Doherty

- Martin Bostock

- Martin Nunn

- Martin Waxman

- Mary Poliakov

- Mary Poliakova

- Masahiro Makiguchi

- Matthew Jervois

- Matthew Moth

- Matt Juniper

- Matt Kucharski

- Matt McKenna

- Matt Peacock

- Matt Thomas

- Maureen Kline

- Md Abdul Quayyum

- Melanie King

- Melissa Arulappan

- Melody Haller

- Mercedes Córdova

- Meredith L. Eaton

- Michaela Paudler-Debus

- Michael Fineman

- Michael Goodman

- Michael Morley

- Michael Tobias

- Michael T. Schröder

- Michele Kling

- Michelle Hampton

- Michelle Mekky

- Michelle Robertson

- Mike Bruhn

- Mike Copland

- Mike Lemon

- Mike Regester

- Mina Jasarevic

- Misako Ohira

- Mitchell Prather

- Mohammad Reza Bagheri

- Mohammed Abed Said El-Astal

- Mohammed A. S. El-Astal (Dr)

- Mohammed El Batta

- Monica Björklund Aksnes

- Monique Hendriks

- Monique Zytnik

- Morgan McLintic

- Mylinh Lee Cheung

- Nancy Bacher Long

- Nancy Glick

- Nanne Bos

- Narda Shirley

- Natalie Maule

- Natalie Mina

- Nataliya Popovych

- Natasha Koifman

- Neeraj Jha

- Neha Jain

- Neil Bayley

- Neil Green

- Nicholas Barnett

- Nicholas Karides

- Nick Braund

- Nick Colwill

- Nick Cowling

- Nick Rabin

- Nick Seymour

- Nick Sharples

- Nicky James

- Nicole Capper

- Nicole Gorfer

- Nicole Reaney

- Nidal Abou Zaki

- Nidal Abou Zaki

- Nigel Heneghan

- Nigel Kennedy

- Nigel Muir

- Nikhil Dey

- Nikolina Ljepava Ph.D.

- Nikos Drandakis

- Nils Haupt

- Nitin Mantri

- Nomalungelo Faku

- Norty Cohen

- Núria Vilanova

- Olav Ljosne

- Olga Podoinitsyna

- Ong Hock Chuan

- Ong Hock Chuan

- Ovidia Lim-Rajaram

- Øyvind Ihlen

- Patricia Clough

- Patricia Obozuwa

- Patrik Schober

- Paul Anthony Larmon

- Paula Pedene

- Paul Mylrea

- Paulo Andreoli

- Paul Seaman

- Paul Taaffe

- Paul Wilkinson

- Pavel Melnikov

- Pazanne Le Cour Grandmaison

- Pedro Cadina

- Peggy Simcic Brønn

- Pelin Kocaalp

- Pender M. McCarter

- Penny Burgess

- Penny Power

- Percy Dubash

- Perry Yeatman

- Peter Bradley

- Peter Goll

- Peter Hehir

- Peter Heydenrych

- Peter Månsson

- Peter Mutie

- Peter Parussini

- Peter Sherwin

- Peter Spurway,

- Peter van der Merwe

- Peter Walker

- Peter Walshe

- Phil Borge-Slavnich

- Phil Carpenter

- Phil Hampton

- Philip Dewhurst

- Philippe Borremans

- Philip Sheppard

- Philip Tate

- Phil Lobel

- Pia Desai

- Pia Desai Pasricha

- Piers Finzel

- Piers Schreiber

- Piotr Czarnowski

- Polka Yu

- Prema Sagar

- Rachana Panda

- Rachel Bell

- Radhika Shapoorjee

- Rafiat Gawat

- Rahaf Badaro

- Rainer Westermann

- Raju Narisett

- Rakhee Lalvani

- Ralf Leinemann

- Ralf Weber

- Ramya Sahasranaman

- Rania Azab

- Raoul Shah

- Raphaël Mazet

- Rašeljka Maras Juričić

- Rašeljka Maras Jurièiæ

- Rashmi Soni

- Raymond Frenken

- Rebecca Wilson

- Rebecka Blomberg

- Reema Sarin

- Regine le Roux

- Reid Walker

- Rémy Debrant

- Renata Cosby

- Ren Bowman

- Renu Snehi

- Richard Benson

- Richard Brett

- Richard Edelman

- Richard Jukes

- Richard Linning

- Richard Millar

- Richard Northcote

- Richard Tsang

- Richard Waters

- Rich Young

- Risë Birnbaum

- Rishi Bhattacharya

- Rita Malikouti

- Rita Marie Devin

- Roberta Graham

- Robert Hastings

- Robert Held

- Robert Heldt

- Robert H Holdheim

- Robert Phillips

- Robert W. Grupp

- Rob Faulkner

- Rob Gray

- Rob Shimmin

- Robyn de Villier

- Robyn Sefiani

- Rochelle Ford

- Rodney Gray

- Rodolfo Oliveira

- Roger Darashah

- Roger Darnell

- Roger Frizzell

- Roger Hurni

- Roma Balwani

- Romeo P. Virtusio

- Ronald Mincheff

- Ron Childs

- Ron Finlay

- Ron Jabal

- Ronke Lawal

- Ronnie Simpson

- Ronn Torossian

- Ron Sereg

- Rosa María Torres Valdés

- Ruxandra Catalina Dorobeti

- Saada Hammad

- Sabine Einwiller Ph.D.

- Sabine Raabe

- Saeed Philsouphian Ph.D.

- Sally Maier-Yip

- Salvador da Cunha

- Salvatore Ricco

- Samantha Strauss

- Samantha Watt.

- Sandra Macleod

- Sandra Macleod

- Sandra Sinicco

- Sandra Wills Hannon

- Sandy Lish

- Sarah Milner

- Sarah Robarts

- Sara Render

- Saskia Stolper

- Sconaid McGeachin

- Scott Bowers

- Scott White

- Scott Wilson

- Sean O’Neill

- Seçkin Çetin

- Seema Ahuja

- Senjam Raj Sekhar

- Serda Evren

- Sergi Guillot

- Serina Tan

- Serra Görpe

- Seth Oyer

- Shannon A. Bowen, PhD

- Sharif D. Rangnekar

- Sharmistha Ghosh.

- Sheena Thomson

- Sheena Thomson

- Sheila McLean

- Shilpi Jain

- Shravani Dang

- Siddhartha Mukherjee

- Sietse Pots

- Sigrid de Vries

- Silvia Cambié

- Silvia Pendás de Cassina

- Simeon Mellalieu Ph.D.

- Simon Coughlin

- Simon Lewis

- Simon Lloyd

- Simon Poulter

- Simon Quarendon

- Simon Sproule,

- Simon Warne

- Skye Lambley

- Smitha Virik

- Soe Thu Ra

- Sofia Heidenberg

- Sonya H. Soutus

- Sonya Madeira Stamp

- Sophia Halkidou

- Sophie Armour

- Stacey Jones

- Stacie Nevadomski Berdan

- Starr Million Baker

- Stefan Rollnick

- Stella Wink

- Stéphane Guerry

- Stephanie Roberts

- Stephanie Rudnick

- Stephan Oehen

- Stephen Dupont

- Stephen Elliott

- Stephen Waddington

- Steve Drake

- Steve Harris

- Steve Hoddinott

- Steve Howell

- Steve John

- Steve Kee

- Steven Yong

- Stuart Hurni

- Stuart Maister

- Stuart Maister

- Stuart Neil

- Stuart Smith

- Stuart Thomson

- Stuart Zakim

- Sue Foley

- Sujit Patil

- Sukanti Ghosh

- Sukanti Ghosh

- Suki Thompson

- Sunil John

- Sunil John

- Sunity Maharaj

- Susanna Simpson

- Susan Wood

- Suzanne Ffolkes

- Svetlana Stavreva

- Takashi Inoue

- Takashi Inoue

- Tamara Peæareviæ Sušanj

- Tamir Haas

- Tara Rogers

- Tarek Lasheen

- Tasos Pagakis

- Tatevik Simonyan

- Teodoro “Junie” S. Del Mundo, Jr

- Thebe Ikalafeng

- Thomas J. Madden

- Tiffany Guarnaccia

- Till Achinger

- Tim Gingrich

- Tim Newbold

- Timo Hillbrecht

- Tim Phillips

- Tim Scerba

- Tim Skelton-Smith

- Tina McCorkindale, Ph.D., APR

- Toan Ravenscroft

- Toby Doman

- Tokunboh George-Taylor

- Tolulope Aribisala

- Tom Buchan

- Tom Ho

- Tom Liacas

- Tom Parker

- Tom Watson

- Tom Wells

- Toni Muzi Falconi

- Tony Burgess-Webb

- Tony Jaques

- Tony Jewell

- Tony Langham

- Tony Rasman

- Trevor Gorin

- Trevor Morris

- Trey Watkins

- Tuhina Pandey

- Tyler Kim

- Ulrich Gartner

- Ulrich Gartner

- Ulrich Porwollik

- Valéria Café

- Valerie Di Maria

- Valerie Harding

- Valerie Pinto

- Vali Alibayov

- Varghese M Thomas

- Varsha Marathe

- Veronica Sharp

- Veronique Ferjou

- Vicky Robinson

- Vic Miller

- Victoria Brown

- Victoria Osorio

- Vincent Magwenya

- Vivian Kobeh

- Vivian Kobeh

- Vivian Lines

- Vivien Hepworth

- Walter Nessi

- Warrick Hazeldine

- Wes Himes

- Wilfried Remans

- William Moss

- Yahya Ahmadi

- Yang-May Ooi

- Yvette Sterbenk

- Zeynep Özbil

- Zhenya Pankratieva

- Zsofia Balatoni